Halieutika

The Art of Fishing

The Origins – Echoes of Prehistory and Cradles of Civilization

This section delves into the deep roots of fishing, showing that it was not only a subsistence activity but also one of the first and most important fields for human innovation, cognitive development, and symbolic expression. The need to capture agile prey in a strange and often dangerous environment drove the creation of tools, strategic planning, and social cooperation—all elements that are fundamental to what defines us as human.

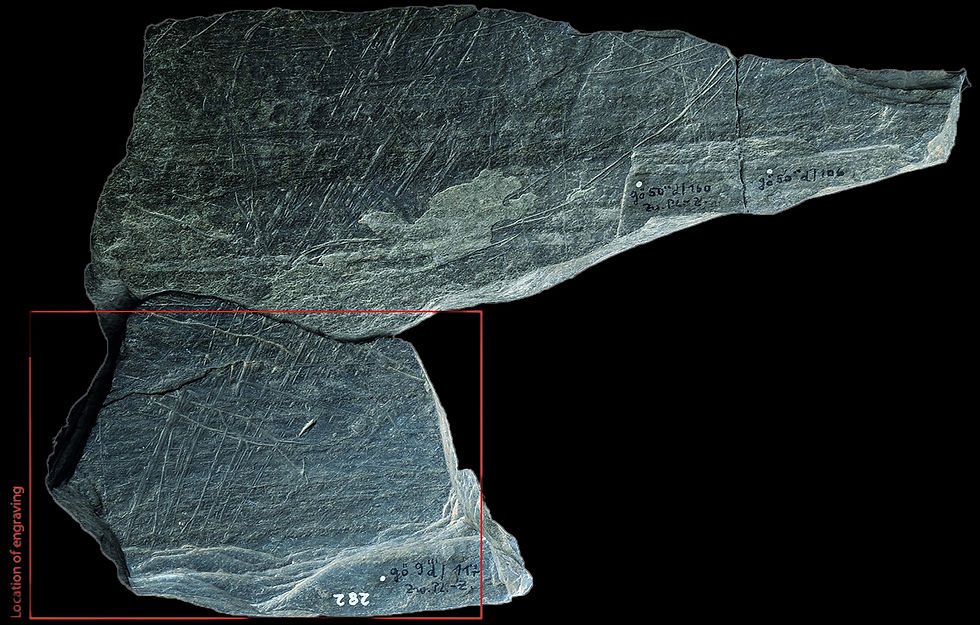

Fishing Net Engraving on a Shale Plate, Magdalenian Artist (c. 15,800 years old). Robitaille et al., 2024.

The First Nets and Fishhooks

Fishing dates back to the Paleolithic era and was a primary activity for life. Besides harpoons and fishhooks, a discovery in Gönnersdorf, Germany, revealed the sophistication of our ancestors. Using RTI imaging technology, engravings on 15,800-year-old shale plates were deciphered, rewriting what we knew about the technology of that time.

The images revealed the oldest representation of fishing with nets, found on plates from the Magdalenian period, showcasing a complex artistic and conceptual process. Artists engraved fish and superimposed a grid pattern to symbolize the catch. This decision to represent the act as mediated by technology, and not just the animal itself, demonstrates a remarkable level of abstract and symbolic thought for the period.

This finding shows that fishing was a catalyst for innovation. The creation of nets in the Upper Paleolithic required a deep knowledge of materials, cooperative planning, and an understanding of fish behavior and currents. Thus, fishing drove engineering and strategy, while techniques such as the use of bone and shell fishhooks would only emerge in the Neolithic period.

Detail with magnification of fishing net engraving on shale plates, Magdalenian Artist (c. 15,800 years old). Robitaille et al., 2024.

Introduction

The word "halieutika," from the Greek halieutikós, is classically defined as "the art of fishing." However, this exhibition proposes a deeper immersion into this concept, exploring its rich duality.

The "art" here is understood in its double meaning: on one hand, the skill, ingenuity, and mastery of the fishing craft—a complex system of empirical knowledge about the cycles of nature, the behavior of species, and the making of tools. On the other hand, it refers to the pictorial representation—art as a record, interpretation, and cultural reflection on this fundamental human activity.

When we look at an illustration of fishing, we see an act of capture as well as a microcosm of culture, social relationships, and accumulated knowledge. Therefore, this exhibition is a journey through this intersection, where the fisherman's gesture and the artist's stroke meet to tell a timeless story.

![[1] EXEA A._Dorph_-_Hornfiskefangst_med_drivvod._Tidlig_morgen_-_KMS1127_-_Statens_Museum_](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b8f352_459b77a38a4c4a3c820aac020b23d15d~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_681,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/%5B1%5D%20EXEA%20A__Dorph_-_Hornfiskefangst_med_drivvod__Tidlig_morgen_-_KMS1127_-_Statens_Museum_.jpg)

![[1] EXEA A._Dorph_-_Hornfiskefangst_med_drivvod._Tidlig_morgen_-_KMS1127_-_Statens_Museum_](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b8f352_459b77a38a4c4a3c820aac020b23d15d~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_681,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/%5B1%5D%20EXEA%20A__Dorph_-_Hornfiskefangst_med_drivvod__Tidlig_morgen_-_KMS1127_-_Statens_Museum_.jpg)

Anton Laurids Johannes Dorph (1880) - Fishing for Garfish Early in the Morning

To begin this journey, two works are presented in counterpoint, establishing the vast range of experiences that fishing encompasses. The first, Fishing for Garfish Early in the Morning (1880), by the Danish artist Anton Laurids Johannes Dorph, envelops us in an atmosphere of calm and cooperation. The soft morning light illuminates a scene of methodical work, where each fisherman plays a role in the operation of the drift net. The work is a testament to fishing as a communal activity, rhythmic with nature, capturing the serenity and beauty of the craft.

In stark contrast, Shark Fishing (1885), by the American Winslow Homer, thrusts us into the center of a drama of strength and danger. The tension is palpable: the agitated sea, the small vessel at the mercy of the waves, and the direct confrontation between man and the powerful sea creature. Here, fishing is portrayed as a struggle for survival, a test of courage and resilience against the brute force of the ocean. Together, these two visions—one of harmony and the other of conflict—define the thematic field of our exploration: the multifaceted and at times contradictory relationship of humanity with the aquatic world.

![[3] EXEA Winslow_Homer_-_Shark_fishing.jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b8f352_e9eb3a0e8dcf4fbd87d58f836151f8a3~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_673,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/%5B3%5D%20EXEA%20Winslow_Homer_-_Shark_fishing.jpg)

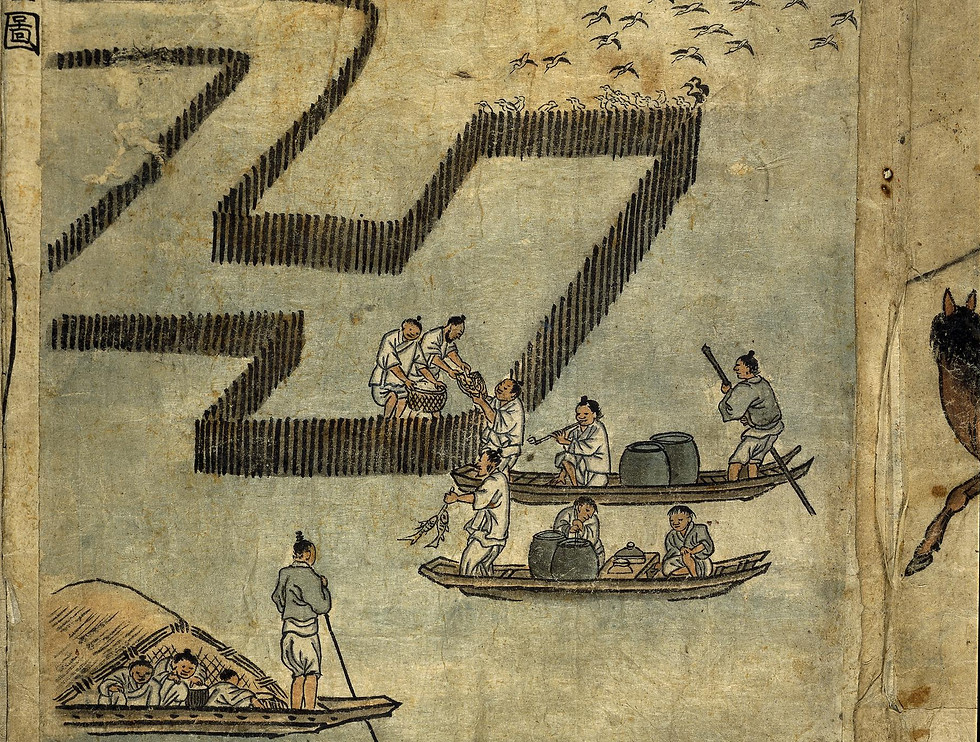

Perhaps the most fascinating of the symbiotic techniques is Cormorant Fishing. Practiced for over 1,300 years, mainly in Japan (ukai) and China, this method involves using trained cormorants. The fisherman, known as an ushō in Japan, ties a snare at the base of the bird's neck, which prevents it from swallowing the larger fish it catches. The bird dives, catches a fish, and returns to the boat, where the fisherman makes it regurgitate the prey. This tradition, recorded in 7th-century Chinese and 8th-century Japanese texts, was so prestigious that it was sponsored by emperors and shoguns, such as Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu, making it a cultural spectacle and a symbol of the symbiotic relationship between humans and animals. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, such as the one by Keisai Eisen (1848), capture the unique atmosphere of this nighttime practice.

Cormorant Fishing on the Nagara River, Keisai Eisen (c. 1848).

Fishing with Light Lures (Torchlight) is a nighttime technique that exploits the positive phototaxis of many fish species. Works such as Night Fishing at the Mouth of a Cave (1828), by an unknown artist, and Torchlight Fishing (1845-1856), by Paul Kane, show how torches and bonfires were used to attract fish to the surface, where they could be easily caught with multi-pronged spears (gigs) or dip nets. This method, practiced in various cultures around the world, turns the darkness of night into an ally for the fisherman.

Torchlight Fishing, Paul Kane (1848-1856).

Fishing Knowledge from the Waters – The Americas, Asia, and Europe

Now we'll look at a brief comparative overview that highlights human ingenuity in distinct ecosystems, observing the techniques and the ways they were represented.

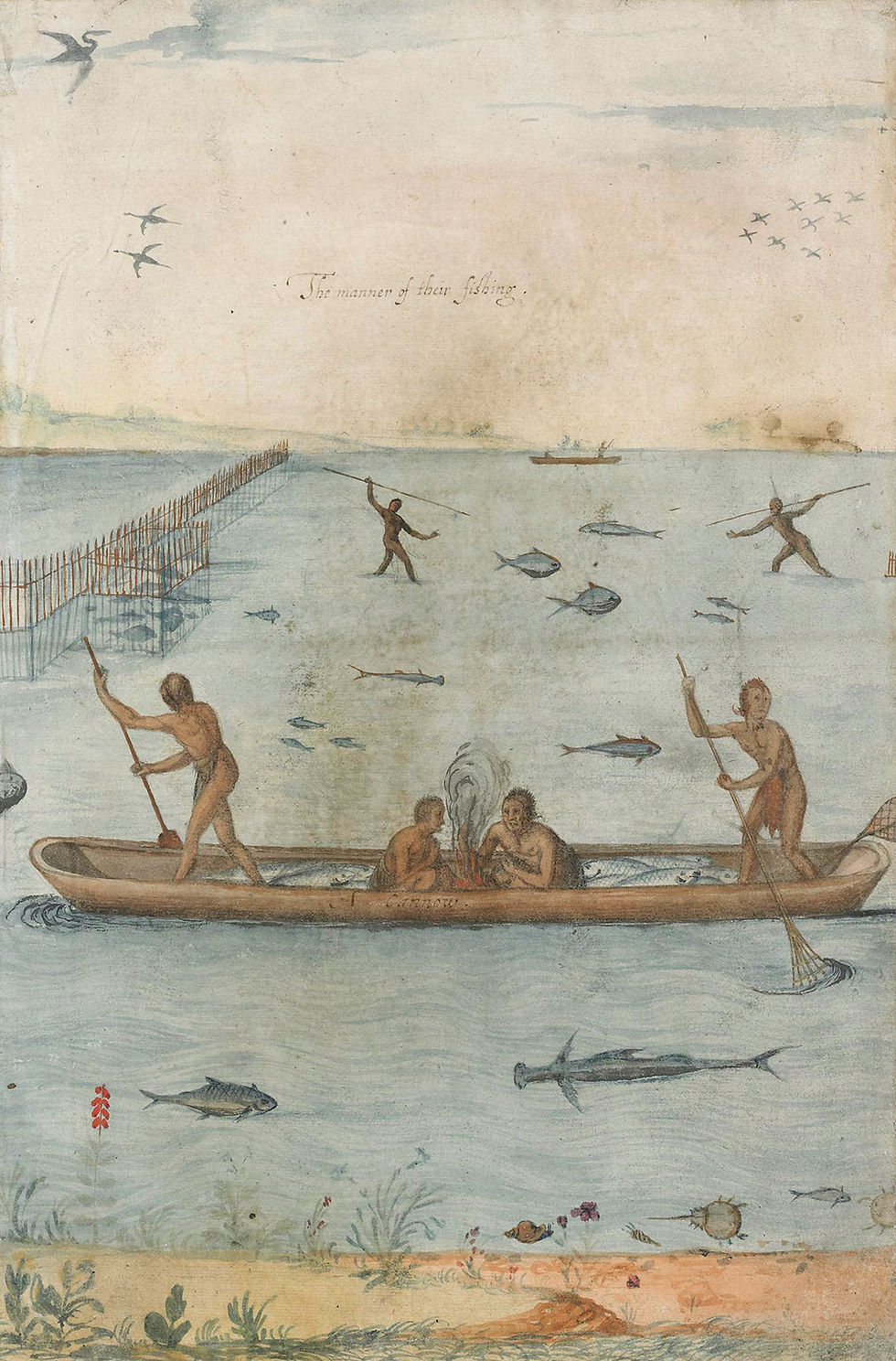

In North America, the watercolors by the English artist John White from the Roanoke expedition (1585-1590) are valuable ethnographic documents. His work, "The Manner of Their Fishing," portrays an efficient indigenous technique using stake weirs to catch fish with spears and dip nets. Analyzing this work, however, requires understanding that it is a European view of the "New World," mediated by a cultural perspective that may have emphasized abundance to promote colonization.

Important ethnographic document about indigenous fishing with weirs in North America. John White, 1580s. Source: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

In Asia, art offers windows into ancient fishing traditions. The Korean painting Fishing, by the memorable artist Kim Hong-do (c. 1745-1806), is an exquisite example. Part of his Album of Genre Paintings, it illustrates corral fishing. In the painting, a large, zigzagging trap made of stakes catches fish in the river.

The scene details community work, where fishermen in boats use baskets to collect the trapped fish. Unlike the external perspective of John White, Kim Hong-do painted for a local audience, celebrating the life and work of common people during the Joseon Dynasty.

![[3] EXEA Winslow_Homer_-_Shark_fishing.jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/b8f352_e9eb3a0e8dcf4fbd87d58f836151f8a3~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_673,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/%5B3%5D%20EXEA%20Winslow_Homer_-_Shark_fishing.jpg)

Winslow Homer (1885) - Shark Fishing.

Fishing in the Great Empires of Antiquity

With the advent of great civilizations, fishing evolved from a subsistence practice into an organized economic activity that was culturally significant and even a topic of literary and philosophical reflection.

In Ancient Egypt, life depended on the Nile, and fishing was central. Representations in tombs and reliefs, such as those of Usheret (c. 1430 B.C.) and Saqqara (c. 2400 B.C.), show techniques using spears and multiple hooks. These works held ritualistic meaning, seeking to ensure sustenance and abundance in the afterlife.

Egyptian fisherman fishing with a spear, Tomb of Usheret (c. 1430 B.C.).

Fishing and Fowling Scene on Limestone, Egyptian (c. 1353-1336 B.C.)

In the Greco-Roman world, fishing permeated culture, from gastronomy to literature. Detailed mosaics, like those found in La Chebba, Tunisia, depict a variety of species and techniques, including the use of pots (basket-shaped traps) and nets, showing a well-established fishing industry. However, the most notable contribution from this period is Halieutika, an epic poem in five volumes written by the Greek poet Oppian of Corycus in the 2nd century A.D.

Halieutika is a complex literary work that describes the behavior of marine species, capture techniques, and the relationship between man and the sea. The work uses the aquatic world—with its species' "wars," "passions," and "wiles"—as a powerful allegory for human society, meditating on the morality of exploiting nature and humanity's place in the cosmos.

Roman (3rd Century A.D.) - Fishing with Pots Mosaic. Source: Archaeological Museum of Sousse, CC BY-SA 3.0.

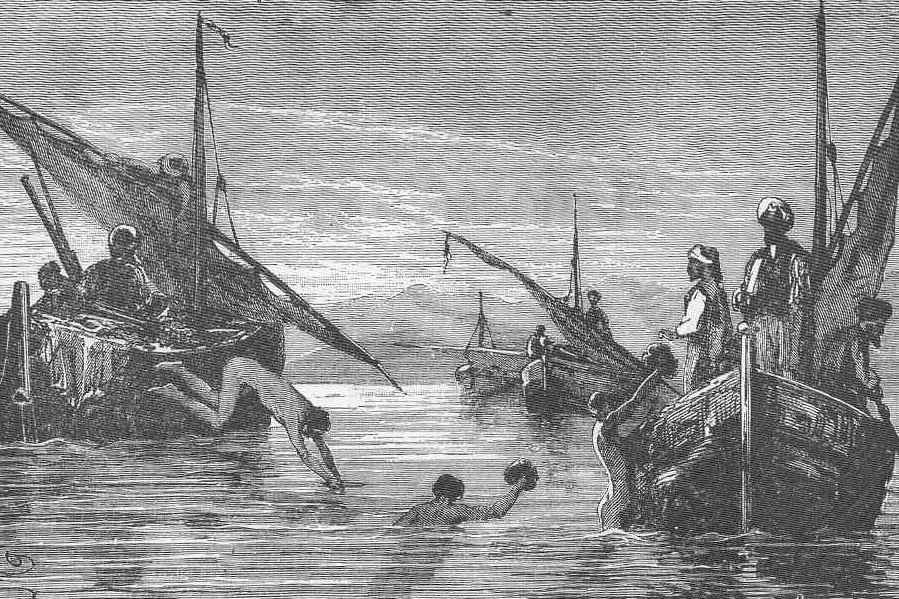

Gathering of Sea Sponges on the Coast of Syria, Leon Sorel (1872).

Unique Techniques and Traditions

We will now highlight fishing methods notable for their specificity and ingenuity, demonstrating unique adaptations to particular ecological or cultural niches.

Manual Gathering and Diving represent the most primordial forms of interaction with aquatic resources. The painting Women Oyster-Gathering at Cancale (1878) by John Singer Sargent, depicts gathering in the intertidal zone, an activity often associated with communal and female labor.

Meanwhile, the engraving Gathering of Sea Sponges on the Coast of Syria (1872) illustrates the ancient and risky practice of free-diving to collect sponges from the seabed, an activity that required extraordinary lung capacity and courage. The manual dredge, as seen in The Fisherman (1883) by Jozef Israëls, represents an evolution of this gathering—a simple tool that allows for "scraping" the bottom in search of mollusks.

In Europe, the painting "Fishing scene, with a royal yacht near the coast" (1768) by the British artist Francis Swaine, transports us to a bustling 18th-century harbor. In the foreground, fishermen are performing a beach seine, an ancestral and collective fishing art where a large net is pulled from the shore. The work juxtaposes the manual labor of the fishermen with the pomp of the royal yacht in the background, highlighting the different social realities that shared the same waters.

Across the Atlantic, in the Aztec Civilization, fishing was equally essential for the survival of the metropolis of Tenochtitlan, which was built on Lake Texcoco. Sources like the Florentine Codex illustrate a variety of methods, such as the use of nets, harpoons, and fishhooks. The most ingenious of their adaptations was the chinampas system. Often described as "floating gardens," chinampas were in fact a sophisticated system of integrated agriculture and aquaculture.

These were artificial islands built from the lake bottom's mud and vegetation, stabilized by trees planted along their edges. The channels between the chinampas not only served for irrigation and transport but also functioned as nurseries for fish and other aquatic organisms, creating a highly productive and self-sustaining ecosystem in the heart of the empire.

"In Tlahtlama: The Fisherman." Book 10, Folio 58v. Richter & Houtrouw (2023).

A Cross-Cultural Look at the Art of Fishing

Abandoning a strict chronology, this section celebrates the extraordinary diversity of solutions that different cultures around the world have developed for the challenge of fishing. It demonstrates how each people's environment, available resources, and worldview uniquely shape the technology, art, and culture associated with this practice.

Dragnet fishing in the Commewijne River, Suriname. Louise von Panhuys (1811-1816).

Kim Hong-do (c. 1745-1806) - Fishing, from the Album of Genre Paintings. Source: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Fishing scene, with a royal yacht near the coast. Francisco Swaine (1768).

John Singer Sargent (1878) - Women Oyster-Gathering at Cancale.

Jozef Israëls (1883) - The Fisherman.

.jpg)

Night Fishing at the Mouth of a Cave, Unknown (1828).

Conclusion

At the end of this journey, we have traveled across millennia and continents, guided by the line, the hook, and the net. We have seen how Halieutika—the art of fishing—manifests itself in two ways: in the ingenuity of fishermen and in the sensitivity of the artists who documented their craft.

From a 15,000-year-old stone engraving to vibrant European painting, each work revealed not just a technique, but also a fragment of human life. We have explored our deep and universal connection with the water and our capacity to adapt, create, and survive.

This exploration is just beginning. Soon, the EXEA Maritime Museum will continue to unravel the secrets of Halieutika, including a deep dive into the epic and dramatic art of whale hunting as depicted on canvas.

We look forward to seeing you for the next catch.

Credits

Exhibition: Halieutika - The Art of Fishing

Ariana Guimarães

Bachelor of Science in Fisheries Engineering / UFRPE

Professor at IFPB / Cabedelo

Researcher at PREAMAR/PB

Ticiano Alves

Bachelor of Science in Fisheries Engineering / UFRPE

Ph.D. in Archaeology / University of Coimbra

Researcher at PREAMAR/PB

Authorship

Ticiano Alves

Exhibition Coordinator EXEA

Maritime Museum

Leandro Vilar

General Director EXEA

Maritime Museum

Curatorship

Ticiano Alves

Exhibition Coordinator EXEA

Maritime Museum

Layout and Design

Juliana Rios

Marketing Coordinator EXEA

Maritime Museum

Exhibition Marketing

Whispers of the Sea (Sussuros do mar)

MusicGen Envato

Background Music

Leandro Vilar

General Director

EXEA Maritime Museum

Camila Rios

Technical Director | Museologist

EXEA Maritime Museum

Raphaella Belmont Alves

Executive Director | Orthographic Reviewer

EXEA Maritime Museum

Exhibition Revision

Museu Arqueológico de Sousse. CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

PINTO, Gislaine. Ukai: a arte japonesa de pesca com aves. Magnus Mundi, 10 fev. 2021. Disponível em: https://www.magnusmundi.com/ukai-a-arte-japonesa-de-pesca-com-aves/. Acesso em: 28 jul. 2025.

Richter, Kim N.; Houtrouw, Alicia Maria . Disponível em Digital Florentine Codex/Códice Florentino Digital, editado por Kim N. Richter e Alicia Maria Houtrouw, "Livro 10: O Povo", fol. 58v, Getty Research Institute, 2023. https://florentinecodex.getty.edu/en/book/10/folio/58v/images/5c4d10a7-435e-40f2-8d93-e3fe026d72c6 Acessado em 24 de junho de 2025 .

Robitaille J, Meyering L-E, Gaudzinski-Windheuser S, Pettitt P, Jöris O, Kentridge R. (2024) Upper Palaeolithic fishing techniques: Insights from the engraved plaquettes of the Magdalenian site of Gönnersdorf, Germany. PLoS ONE 19(11): e0311302. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0311302

The Trustees of the British Museum . Compartilhado sob uma licença Creative Commons Atribuição-NãoComercial-CompartilhaIgual 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) .

Sources and References

© All Rights Reserved.

Legal Curatorship